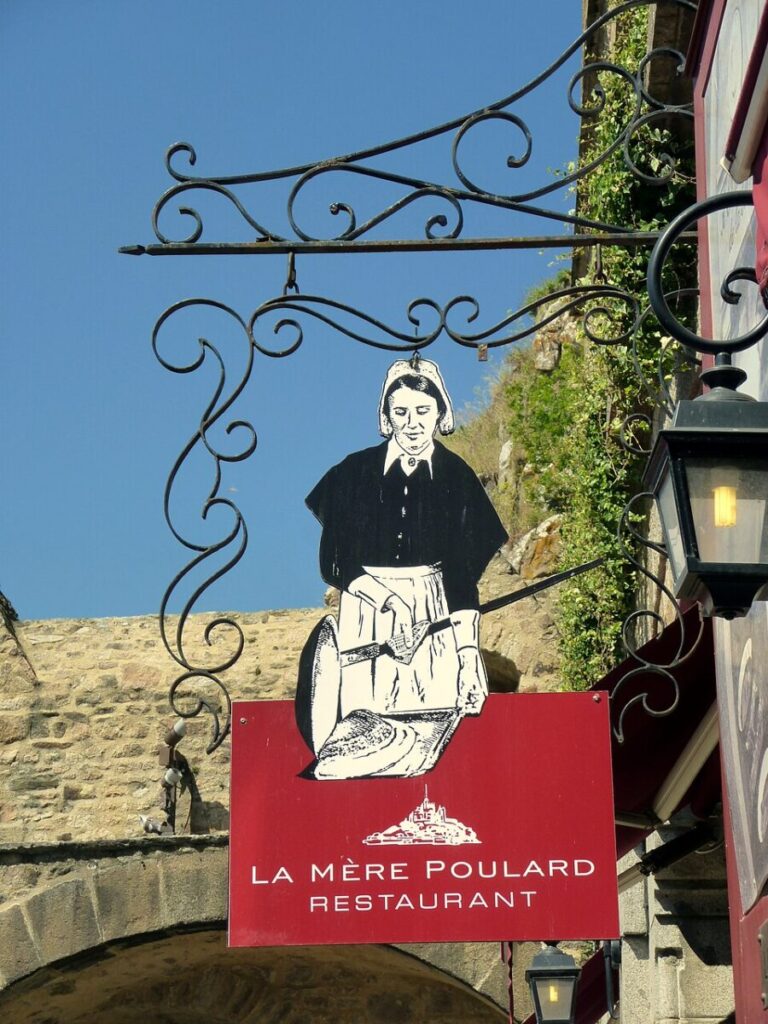

Auberge de la Mère Poulard – France’s most popular omelette

The Auberge de la Mère Poulard opened in 1888 on Mont-Saint-Michel. It was founded by Annette Poulard, who was not a trained chef but an innkeeper responding to very real constraints.

Reaching the Mont in the late 19th century was slow and uncertain. Visitors crossed tidal sands, waited for boats, or arrived after long delays caused by weather. Many showed up late in the day, cold, exhausted, and hungry.

Meals had to be fast, reliable, and based on ingredients that were always available. Eggs and firewood fit that need perfectly.

The omelette

The omelette was never designed as a refined dish, it was practical food for pilgrims and travelers who needed to eat quickly before resting or continuing their journey.

Annette Poulard beat the eggs vigorously to trap air, poured them into a copper pan, and cooked them over a very hot wood fire. The result was tall, soft, lightly set inside, and ready in minutes.

Speed and heat were essential. The dish was about efficiency rather than subtlety.

Open hearth

From the beginning, the omelette was cooked in front of guests. The hearth sat directly in the dining room, not in a back kitchen.

Visitors saw the eggs being beaten, the pan set close to the flames, and the omelette forming in seconds.

By the early 1900s, watching the omelette being made had already become part of the experience of arriving at the Mont.

The myth

The dish is often called a “soufflé omelette,” but that description is inaccurate. There is no oven involved, no whipped egg whites folded in, and no baking step. The height comes from aggressive whisking and intense heat, not from a soufflé technique.

Contemporary accounts describe eggs being beaten by hand for several minutes until the cook’s arm burned. The texture relies entirely on timing and fire control.

Even today, the omelette uses eggs only, with no added cream or stabilizers.

As access to Mont-Saint-Michel improved and tourism increased, the Auberge became a required stop for influential visitors.

King Edward VII of England ate there. Ernest Hemingway followed. Salvador Dalí did as well. French presidents, ministers, and cultural figures came later.

The omelette gradually became a symbol. Eating it marked the moment you had truly arrived at the Mont.

Mass tourism

After the Second World War, tourism changed scale. Visitor numbers exploded, and the omelette shifted from pilgrim food to a high-volume service dish. Prices increased, service sped up, and expectations changed.

Many visitors began judging it as a conventional restaurant meal rather than a historical ritual tied to a specific place. That gap in expectations explains much of the controversy that still surrounds it today.

Despite decades of criticism, changing food trends, and pressure to modernize, the core elements never changed.

The omelette is still cooked over a real wood fire. Copper pans are still used. The cooking still happens in front of guests, in the same visible space.

There are no electric plates, no hidden shortcuts, and no modern reinterpretation of the technique.

Final words

At the end of 2025, the La Mère Poulard group sold its biscuit factory to stop running two very different businesses at the same time. The focus is now on Mont-Saint-Michel and Auberge de la Mère Poulard.

The group plans to fix crowd flow, reduce the assembly-line feeling during rush hours, and standardize omelette training so results stay consistent despite staff turnover.

For travelers, the La Mère Poulard experience stays what it has always been: the same omelette, cooked the same way, in the same place, but run with more control as visitor numbers keep climbing.