The Pétain Tribute Mass in Verdun That Sets Off France

Verdun doesn’t usually spark national headlines, but this week it did.

A simple announcement in a parish church touched a raw part of French history, and the reaction spread quickly. The name involved was enough to push the story far beyond local news.

What Sparked It

A religious association planned a mass on 15 November at Église Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Verdun. The event was announced as a tribute to Marshal Pétain and his soldiers. For anyone familiar with French history, that wording hits hard.

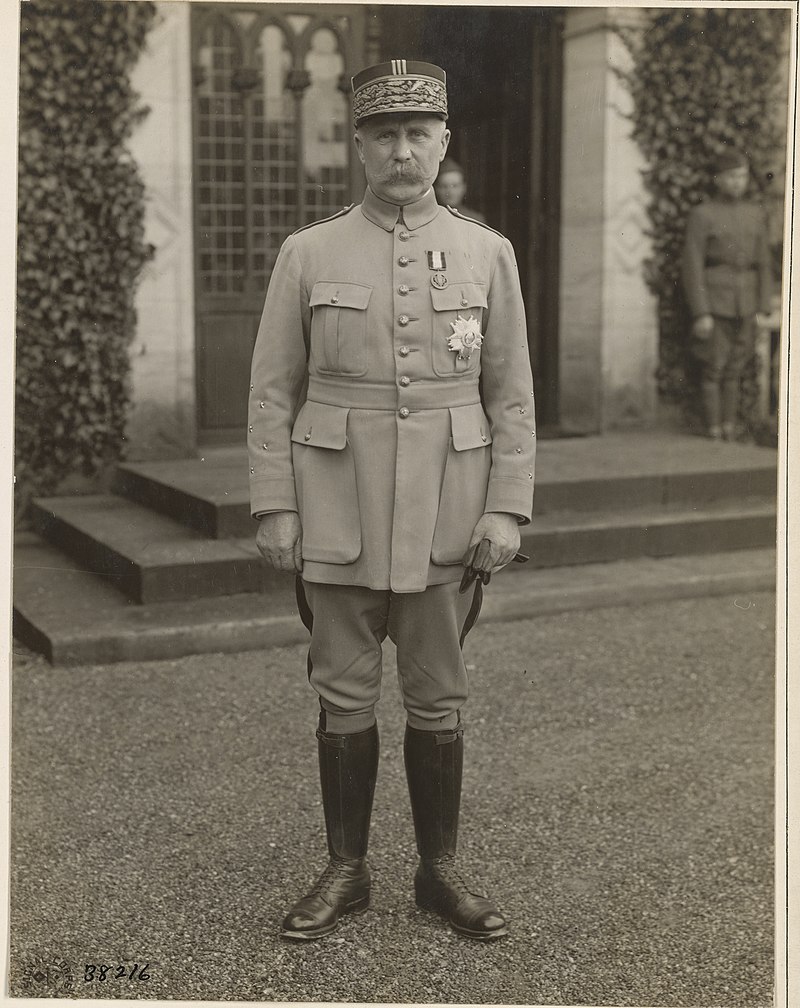

Pétain carries two legacies. The first: a World War I commander who held the French line at Verdun in 1916.

The second: the head of Vichy France in World War II, responsible for collaboration with Nazi Germany and the antisemitic legislation that followed.

A tribute in Verdun, of all places, reignited the question France never fully escapes: can the “hero of Verdun” be separated from the man who led Vichy? And should he be honoured in a city that symbolises national sacrifice?

Verdun is one of France’s strongest symbols of suffering and national endurance. More than 300,000 soldiers died or were wounded there in 1916. The entire region is marked by forts, ossuaries, and cemeteries.

The Mayor Tried to Ban It

Samuel Hazard, the mayor of Verdun, issued a decree forbidding the ceremony.

He argued that Pétain had been condemned after the war and stripped of his honors, and that the tribute risked fueling tensions at a moment when antisemitic acts are rising in France.

To him, the event was political, not religious.

The association behind the mass, the ADMP (Association pour défendre la mémoire du maréchal Pétain) challenged the ban and pointed to the Church’s authorization. They framed the ceremony as a WWI commemoration.

On 14 November, however, the administrative court in Nancy suspended the mayor’s decree. The judges said the city had not shown concrete evidence of a public-order threat, which is required to justify such a ban.

The mass was allowed to go ahead under police presence. And the legal victory gave the event even more visibility than the organizers could have created themselves.

What Actually Happened in the Church

On the day of the ceremony, roughly twenty people entered the church.

Outside, around a hundred protesters gathered.

The numbers mattered: the tribute itself was small. The reaction around it was not.

Yonathan Arfi, president of the Crif – France’s main national organisation representing Jewish institutions – condemned the tribute sharply.

He called it an “injury to the memory” of deported Jews and described the mass as “apologie de la collaboration.”

He reminded that on 15 August 1945, Pétain was convicted of intelligence with the enemy, high treason, and national indignity.

Honoring him today, he wrote, was a betrayal of the Republic.

Arfi also tied the moment directly to the 76,000 Jews deported from France under Vichy. In his words, celebrating a mass for Pétain “rehabilitates a traitor to the country.”

These statements pushed the story firmly into the national spotlight.

The Prefect Steps In

The préfet de la Meuse announced an article 40 referral to prosecutors after hearing revisionist statements made outside the church.

Interior minister Laurent Nuñez expressed support for the Verdun mayor and condemned any attempt to rehabilitate figures tied to collaboration.

This administrative step added another layer to the day: the event was no longer just a symbolic dispute but a case with legal follow-up.

The ADMP’s Position

After the ceremony, Jacques Boncompain, president of the ADMP, told journalists that Pétain had been “the first resistant of France.”

This statement is typical of the group’s long-running strategy: pushing Pétain’s WWI image to overshadow his later responsibility as head of Vichy.

Their events regularly trigger clashes with local authorities, and the Verdun mass fits that pattern.

How People Interpreted It

Opponents see any tribute as an attempt to soften or erase Vichy’s role in French history.

Supporters insist the ceremony was limited to WWI.

Neither side sees the other as neutral, which is why these debates grow quickly.

In Verdun, the symbolic weight of the location amplified everything: what might have been a niche event elsewhere became a national confrontation in a single day.