The Man Who Saved the Louvre

In late August 1939, with German troops massing near the French border, a quiet civil servant began a mission that would save France’s cultural soul. His name was Jacques Jaujard.

He wasn’t a soldier or a politician, but by the time Paris was liberated six years later, his secret operation would ensure that not a single masterpiece from the Louvre fell into Nazi hands.

Preparing for War in the Halls of the Louvre

Jacques Jaujard was 44 years old when the war clouds gathered. As Director of National Museums, he oversaw the Louvre, the Musée du Luxembourg, and others.

He had seen how Nazi Germany had plundered art collections in Austria and Czechoslovakia. He knew France would be next. Long before the French government issued any evacuation orders, Jaujard quietly began his own.

He gathered trusted curators, including René Huyghe, Rose Valland, and Germain Bazin, and drew up plans to empty the Louvre under the pretext of “protective measures.”

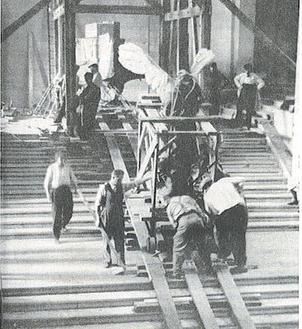

On August 25, 1939, the first crates appeared in the museum’s courtyards. Over 4,000 works including the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, and Winged Victory of Samothrace were taken down from their pedestals and walls.

Even the massive paintings by Veronese and Delacroix were unframed, rolled, and packed away. The museum closed to the public “for renovations.”

Each crate bore a color code for its destination. In total, thirty-seven convoys of trucks, escorted by gendarmes, slipped quietly out of Paris over the next three days.

The Secret Convoys of 1939

The first stop was the Château de Chambord, deep in the forests of the Loire Valley. Its thick stone walls and remote location made it a natural fortress.

There, the Louvre’s treasures were stored temporarily before being dispersed further south and west as the front lines shifted.

The Mona Lisa traveled in a specially designed case padded with velvet. She was transported upright, wrapped in silk, and handled only by two people.

In the years that followed, she would be moved six times, to Amboise, Louvigny, Montal, and finally to the Abbaye de Loc-Dieu near Rodez, each time accompanied by coded orders and Jaujard’s personal oversight.

Even during the chaotic German advance of 1940, the convoys continued. Curators hid smaller works in private estates and remote monasteries.

Jaujard coordinated everything from Paris, using coded telegrams and falsified paperwork. His cover story: “Routine museum transfers.”

The Nazis Arrive in an Empty Museum

When German troops marched into Paris in June 1940, the Louvre was already empty. The marble floors echoed under their boots. Empty frames hung on the walls, labeled as if awaiting restoration.

Hermann Göring, obsessed with art looting, sent agents from the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) to take inventory. They were furious to find nothing.

Jaujard feigned cooperation, presenting incomplete lists and claiming that all artworks had been moved to “safe storage” in the south under government control.

His main opponent-turned-ally was Count Franz von Wolff-Metternich, a German officer in charge of protecting cultural property. Unlike Göring’s looters, Metternich was an art historian who privately respected Jaujard’s courage.

He slowed down inspections and occasionally “lost” documents that could have revealed the hiding places.

Jaujard played a delicate game, appearing compliant enough to avoid arrest, yet obstructing every German attempt to recover the art.

When a Nazi inspection team got too close to Chambord, he ordered emergency relocations deeper into the countryside.

Years of Deception and Hidden Risks

During the Occupation, Jaujard continued to oversee France’s museums from a modest office on the Rue de Rivoli. He relied on a small circle of loyal staff and on Rose Valland, a museum curator secretly recording every German art shipment leaving Paris.

Together, they built a network that documented stolen works while keeping French ones safe.

Conditions were harsh. Some châteaux were unheated and damp. Curators had to light fires in front of stacked crates to prevent mold from damaging the canvases. Paintings were regularly unpacked and inspected by candlelight.

When rumors spread that the Germans might confiscate the Winged Victory of Samothrace, Jaujard ordered it moved again, at night, under tarpaulins, with the sound of distant gunfire in the hills.

He knew discovery could mean prison or worse. But his sense of duty overruled fear. “We are the guardians of civilization,” he once told a colleague. “It is our task to keep it alive.”

Liberation and the Return of the Masters

When Paris was liberated in August 1944, Jaujard returned to the Louvre within days. Dust covered the floors; bullet holes marked the façade. But the art, the lifeblood of France, had survived.

Convoys began returning from the countryside under military escort. Workers unpacked masterpieces that hadn’t seen daylight in years.

The Mona Lisa arrived back in Paris in June 1945 to be reinstalled under heavy guard. Nothing was missing. Nothing was looted.

Jacques Jaujard received the Légion d’Honneur for his wartime service, though he rarely spoke about what he had done. He resumed his museum duties quietly, without speeches or interviews.

A Silent Hero

For decades, his story remained obscure. Only in recent years did France fully honor him through exhibitions, archives, and the 2015 documentary Illustre et Inconnu: Comment Jacques Jaujard a Sauvé le Louvre.

He died in 1967, buried without fanfare. Yet every visitor walking through the Louvre today, every glance at the Mona Lisa or the Winged Victory, is part of his legacy.

When Europe descended into darkness, Jaujard’s courage kept the light of art alive. He fought with intelligence, precision, and quiet defiance. The Louvre stands today because one man refused to let beauty disappear into war.