The Real Names of Paris Arrondissements

Most people see Paris as a simple numbered map, but few people know every arrondissement has an official name set on 16 June 1859.

Those names weren’t decorative, they reflected monuments, political power, science, vanished buildings, and villages absorbed into the city.

Once you know them, the layout of Paris reads like a timeline.

Louvre, Bourse, Temple, Hôtel-de-Ville, Panthéon

The 1st is Louvre. The name comes from the medieval fortress built under Philippe Auguste in the 1100s and expanded by Charles V in the 1300s.

Long before it became a museum, it was the heart of royal power.

The 2nd is Bourse. It refers to the Palais Brongniart, seat of the Paris stock exchange from 1826. This arrondissement is also the smallest in the city, with only 99 hectares.

The 3rd is Temple. It takes its name from the vast Templar compound that once stood there. This was the headquarters of the Knights Templar in France, a fortified district with its own laws and treasuries.

The 4th is Hôtel-de-Ville. It refers to the city hall at the corner of rue de Rivoli and rue de Lobau. The site has been the center of municipal authority since the Middle Ages.

The 5th is Panthéon. The name comes from the grand monument on the hill built for Louis XV and later turned into a national mausoleum after the French Revolution.

Luxembourg, Palais-Bourbon, Élysée, Opéra

The 6th is Luxembourg. It takes its name from the palace built by Marie de Médicis in the early 1600s, today the seat of the Senate.

The 7th is Palais-Bourbon. Originally a princely residence, it became the home of the National Assembly and a symbol of legislative power.

The 8th is Élysée. Its name comes from the Élysée Palace, finished in 1722 and turned into the official presidential residence in 1848.

The 9th is Opéra. But not because of the Palais Garnier. It was named after the Opéra Le Peletier, the city’s main opera house from 1821 until it burned down in 1873.

Entrepôt, Popincourt, Gobelins, Observatoire

The 10th is Entrepôt. The arrondissement once contained the central customs warehouse on rue Léon-Jouhaux. This depot processed goods entering the capital and shaped the area’s working-class identity.

The 11th is Popincourt. The name comes from Jean de Popincourt, president of the Parliament of Paris in the early 1400s.He built his manor here, and a hamlet grew around it.

The 13th is Gobelins. The Gobelin family were dyers who arrived in the 1300s and built a workshop that later became the royal tapestry manufactory. Their name survived every urban change.

The 14th is Observatoire. It refers to the Paris Observatory, founded in 1667 and still active today. Its location fixed the southern line of the arrondissement.

Vaugirard, Passy, Batignolles-Monceau, Buttes-Montmartre

The 15th is Vaugirard. It was a separate commune before annexation in 1860.

It is still the most populated arrondissement.

The 16th is Passy. Once a spa village known for mineral springs and countryside retreats, it was absorbed during Haussmann’s expansion.

The 17th is Batignolles-Monceau. A pair of former villages that merged into the growing city.

The 18th is Buttes-Montmartre. The name refers to the hilly terrain shaped by gypsum quarries long before artists arrived.

The 19th is Buttes-Chaumont. It takes its name from the steep heights that later became the park inaugurated under Napoleon III.

The 20th is Ménilmontant. A hillside hamlet named for its rising slope (“montant”).

It was once known for vineyards and windmills.

Reading Paris through its official names

The 1859 decree didn’t just assign labels, it preserved what Paris considered essential at the time: royal seats, political halls, scientific institutions, cultural landmarks, and entire villages pulled into the expanding capital.

Most visitors never hear these names, but they show exactly how Paris became the city mapped by numbers today.

How the quartiers fit into the map you see

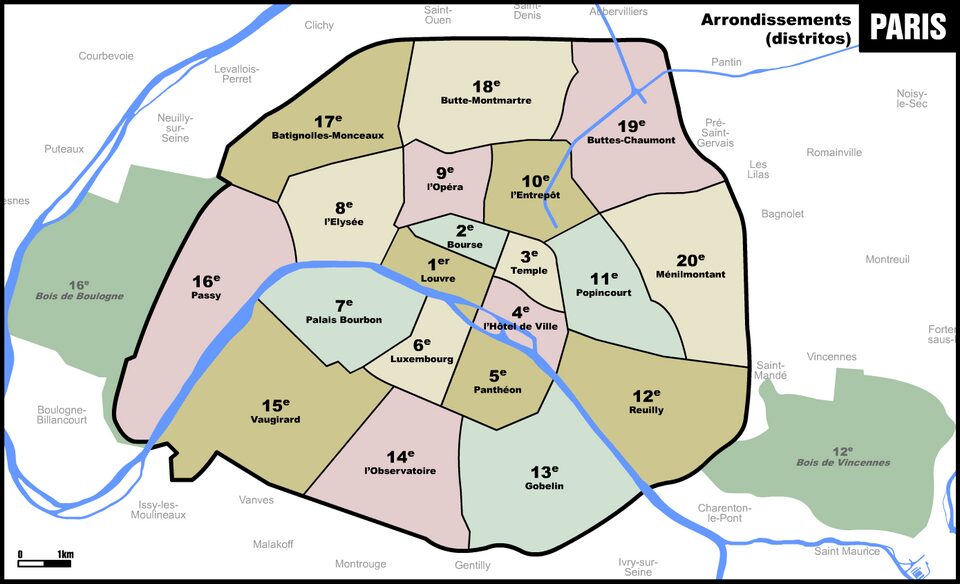

Each arrondissement is also divided into four administrative quartiers. They appear on many maps like the one shown here, and they often have names that feel more familiar than the official arrondissement titles from 1859.

These quartier names were set long before modern Paris took shape, and many come from old parishes, historic streets, small hamlets, or geographic features that existed centuries ago.

This means every arrondissement actually has two naming layers.

The official name, like Louvre or Gobelins, rarely appears in daily life.

The quartier names, like Arts-et-Métiers or La Chapelle, show up more often on maps and local documents.

They help explain how each part of the city grew: medieval trade areas, old villages absorbed by the 1859 expansion, industrial zones, working-class pockets, or former religious districts.

Most maps highlight the quartiers rather than the official arrondissement names. So when you look at the map here, you’re seeing the internal layout of each arrondissement rather than the historic names tied to the 1859 decree.

Both systems overlap on the same territory, but they tell two different stories: one about the city’s political reorganization, the other about its older local identities that survived inside the modern borders.